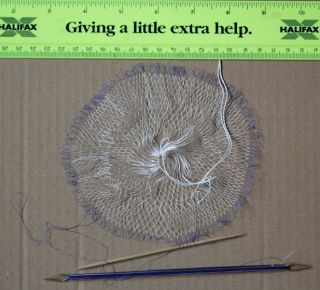

Yesterday's post brought up a question in the comments regarding whether the fillet with the pie-crust edge was closed on top or not... good question.

Personally, I tend to see all of the fillets as open on top unless I can clearly see otherwise. That is possibly due just to a personal quirk, but my reasoning is: You don't really need it closed on top for stability (stiff linen holds up just fine even without an inlay of leather, or felt, or whatnot), and it's easier to adjust in size if you don't close it. So you can have a strip of linen that you tack together or even just hold together with a needle in the back, and if your hair changes or your hairstyle changes or you have a thicker barbette... adjusting the size is no big deal. Also it saves material.

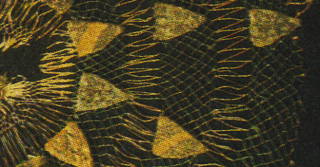

There is one non-typical fillet in the codex Manesse that shows, very clearly, a non-closed version:

(fol. 11v, or page 18)

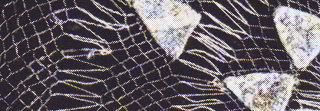

I have also tended to see the little darker area on top of this fillet as the top of the head peeking through:

(fol. 32v)

The only closed headdress find I know is one from Villach-Judendorf; that one has, however, no pie crust and consists instead of gold-brocaded narrow ware. Beautiful - but quite different from the Manesse versions.

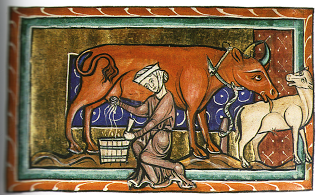

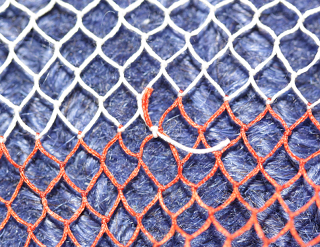

Finally, while there is no picture of b-and-f in the Manesse clearly showing the top of the head peeking through, there is also none clearly showing a fabric top. And there are quite a few pictures clearly showing the fillet as just a strip, such as this one:

(pic out of HÄGERMANN, D. (Ed.) (2001) Das Mittelalter. Die Welt der Bauern, Bürger, Ritter und Mönche., RM Buch und Medien.; late 13th c, England).

That's my thoughts about the question hat or band as fillet - I'd be happy to hear your opinion, and the reasons for your arriving there!

Personally, I tend to see all of the fillets as open on top unless I can clearly see otherwise. That is possibly due just to a personal quirk, but my reasoning is: You don't really need it closed on top for stability (stiff linen holds up just fine even without an inlay of leather, or felt, or whatnot), and it's easier to adjust in size if you don't close it. So you can have a strip of linen that you tack together or even just hold together with a needle in the back, and if your hair changes or your hairstyle changes or you have a thicker barbette... adjusting the size is no big deal. Also it saves material.

There is one non-typical fillet in the codex Manesse that shows, very clearly, a non-closed version:

(fol. 11v, or page 18)

I have also tended to see the little darker area on top of this fillet as the top of the head peeking through:

(fol. 32v)

The only closed headdress find I know is one from Villach-Judendorf; that one has, however, no pie crust and consists instead of gold-brocaded narrow ware. Beautiful - but quite different from the Manesse versions.

Finally, while there is no picture of b-and-f in the Manesse clearly showing the top of the head peeking through, there is also none clearly showing a fabric top. And there are quite a few pictures clearly showing the fillet as just a strip, such as this one:

(pic out of HÄGERMANN, D. (Ed.) (2001) Das Mittelalter. Die Welt der Bauern, Bürger, Ritter und Mönche., RM Buch und Medien.; late 13th c, England).

That's my thoughts about the question hat or band as fillet - I'd be happy to hear your opinion, and the reasons for your arriving there!