About every year around the same time, there's pictures of our willow fence, I think.

I've always liked the idea of a living fence - and even though we have a non-living additional fence around our place, the willow one is the higher one, and the more visible one, and the more exciting one.

It's also planted a little bit too close to the actual border of our garden, which, in retrospective, was not the brightest of all ideas. We had thoroughly underestimated how far the new shoots would branch out over the street, and how many of them there would be. We're handling this now by trying to guide everything as straight up as possible with the help of strings; the trick is to tie those in while the new growth is still green and fresh and very malleable.

We planted the fence back in April 2012, when it looked like this:

It's a kind of willow suitable for making baskets, which was important to us - after all, if you cut back the new rods every year, it would be sad if they weren't useful in some way.

Now it looks like this:

The fence, over the years, has taught me a few things. Among them, first and foremost: Even if willows are bendy, and even if you try to get the shapes all nice and even and just so, they are living things and they will react differently. Some will grow more, some will grow less, some will die off. Nothing will be just as accurate as planned, and planted. And in some places, you'll just have to live with something looking different because of a missing bit.

There's limits to what the trees will accept, and the more horizontal you try to make something grow, the closer you get to this limit. Parts of the tree may go up and die suddenly. The low arches are an issue every year, with plenty of them growing only to about the thirdway point, and then the tree puts everything into the new rods and we end up with a dead part beyond.

Another funny thing is when two trees meld together at their contact point. (That was what I had, in my youthful optimism, planned for all of them to do, by the way.) Sometimes, nothing extraordinary happens. Sometimes, though, the new united tree then decides some part of it is not necessary anymore... and there's another bit of dead wood for us to prune off.

What is really fascinating, though, is the difference between the "before" and the "after" harvesting the rods, and how much biomass this fence puts out every year.

Here's the before look:

And here the after, of approximately the same bit:

Every. Single. Year. Amazing, isn't it?

Here's this year's yield, all bundled up. Want to guess how many kilograms of willow?

I've always liked the idea of a living fence - and even though we have a non-living additional fence around our place, the willow one is the higher one, and the more visible one, and the more exciting one.

It's also planted a little bit too close to the actual border of our garden, which, in retrospective, was not the brightest of all ideas. We had thoroughly underestimated how far the new shoots would branch out over the street, and how many of them there would be. We're handling this now by trying to guide everything as straight up as possible with the help of strings; the trick is to tie those in while the new growth is still green and fresh and very malleable.

We planted the fence back in April 2012, when it looked like this:

It's a kind of willow suitable for making baskets, which was important to us - after all, if you cut back the new rods every year, it would be sad if they weren't useful in some way.

Now it looks like this:

The fence, over the years, has taught me a few things. Among them, first and foremost: Even if willows are bendy, and even if you try to get the shapes all nice and even and just so, they are living things and they will react differently. Some will grow more, some will grow less, some will die off. Nothing will be just as accurate as planned, and planted. And in some places, you'll just have to live with something looking different because of a missing bit.

There's limits to what the trees will accept, and the more horizontal you try to make something grow, the closer you get to this limit. Parts of the tree may go up and die suddenly. The low arches are an issue every year, with plenty of them growing only to about the thirdway point, and then the tree puts everything into the new rods and we end up with a dead part beyond.

Another funny thing is when two trees meld together at their contact point. (That was what I had, in my youthful optimism, planned for all of them to do, by the way.) Sometimes, nothing extraordinary happens. Sometimes, though, the new united tree then decides some part of it is not necessary anymore... and there's another bit of dead wood for us to prune off.

What is really fascinating, though, is the difference between the "before" and the "after" harvesting the rods, and how much biomass this fence puts out every year.

Here's the before look:

And here the after, of approximately the same bit:

Every. Single. Year. Amazing, isn't it?

Here's this year's yield, all bundled up. Want to guess how many kilograms of willow?

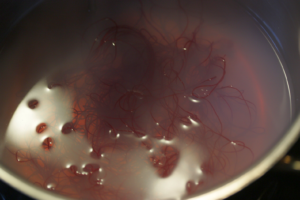

During the de-gumming process - it's starting to lose some of the colour to the soap soup.

During the de-gumming process - it's starting to lose some of the colour to the soap soup.