Here's a comparison of a mockup tunic with slits cut in, with and without middle gores around those slits:

Well, the horse is missing from those images (due to lack of handy horses around here), but you can see that the slit functions, of course, in both instances - with and without a middle gore. However, the version with gores remains much more "closed" even in the riding position. Especially noticeable in the view on the back, where the slit is not visible even in this leg position.

The whole issue gets properly interesting, though, when you are standing normally:

As you can see, the tunic does not close properly at the back if there's no middle gore inserted. This is standing position; the slit issue gets worse, and more noticeable, once the wearer starts to move - when walking or running, the slit will gap open, unless you insert the middle gore.

So that's something you'd definitely want to do for your coverage. Not only to avoid flashing your undies, but also because the slit, staying open, will make things rather drafty in cooler weather!

What you can also see in those standing position pictures is that the fall of the tunic changes with the insertion of the gores. This is significant because riding slits are closely related to riding, which means horses, which is an expensive and status-y thing to have not just today, but also in the Middle Ages. Owning a horse that is used for riding is not something everyone can afford.

Consequently, if you're wearing a tunic with riding slits, that indicates that you have a certain amount of wealth, being a horse-rider. If that changes the fall of your tunic... it's not a big thing to insert a middle gore, with or without slit, leading to the same fall of the tunic regardless of being a horse-rider or not. So that could be an explanation for the middle gore to be found in men's tunics, whether slitted or not, but not in women's dresses.

From the archaeological record, I know of no garment that is certainly associated with a woman with middle gores set in. There's piecings for panels in some of the later dresses (like the Golden Gown of Queen Margaret) that sit in the center front, but they do not change the fall and drape of the garment away from the straighter, more slender silhouette in the front. The fall-changing middle gore is never present. There's also no example of a slit tunic without a middle gore.

To me, this makes perfect sense - you do not need a riding slit in a woman's dress (the bunch-up problem is solved differently, if the woman does ride a horse), but you want the slender look that is easier to achieve with a straight front and back panel in your dress. In men's garments, if you cut in a slit, you definitely need the gore to cover up the unmentionables; that changes the tunic to give it a different fall and drape. That, in turn, may have been associated with a "manly" look, or with higher status, or both, and said associations probably led to the universal adoption of the middle gore in men's garments.

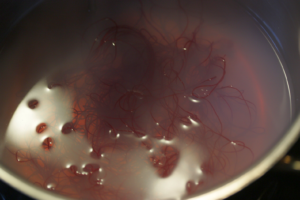

During the de-gumming process - it's starting to lose some of the colour to the soap soup.

During the de-gumming process - it's starting to lose some of the colour to the soap soup.