Because the spiralled net was more or less a practice piece (to try out spiralling and to get my fingers back into netting) and because netting really is a surefire way to attract attention to textile works while keeping the mind unoccupied enough to chat with people, I started a new net right away in Freienfels.

It has the same huge 4 mm mesh size, but is worked with much thinner thread, so it's much closer to historical pieces. The thread might still be thinner, and the mesh could be smaller, but I'll take it slowly for a change. Plus it's not so easy to get superthin yet resilient silk thread.

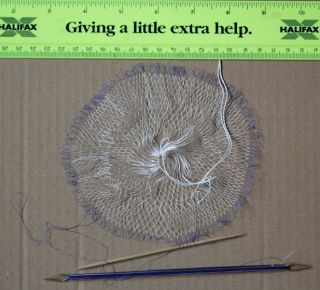

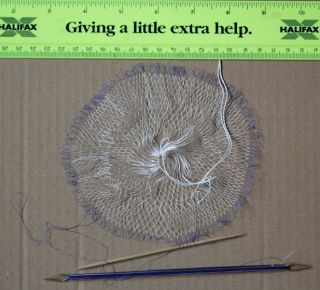

Here you see the new net after nine hours of work. Cast-on went a lot smoother this time, since I stuck to the tried and tested method described by Therèse de Dillmont. Even though, it felt really fiddly due to the thin, fly-away threads (and since I did this out of doors, there actually was some wind to "help" from time to time). I'd say that netting with the fine thread does take a bit longer than with the thicker thread, even with identical mesh size and numbers, because the thin silk likes to crumple or curl up, and I'm a bit more careful with the fine net than with the sturdier one. Hence a little less work speed.

Cast-on loops are about 2 cm long, and cast-on was on a thick linen ply. A second loop of the linen thread serves as holding loop. I have switched completely to working with my new "Nähstein" now that I have finished making it. In case you didn't ever hear of that before, a Nähstein is a weighted pincushion that serves as the third hand to hold netting work or sewing work - and it's so practical! I'll post a picture of the Nähstein in action as soon as I get somebody to take it.

The new net is worked in YLI Silk 100, with the same netting needle and the same mesh stick that I used for the last one (hence the same mesh size). It is worked in the round, and on this picture you can or cannot see the meshes where transition into the next row takes place. Click on the picture to see it larger. Making one full round with the full number of mesh loops takes me about half an hour - so you can go ahead and try to calculate how long the whole thing would take with straightforward netting all through.

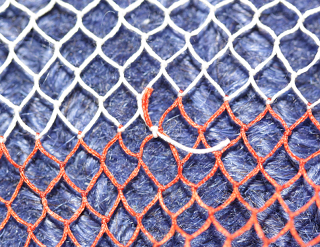

I used the hairnet with the embroidered arms as an inspiration - that is why you see the first rounds of blue netting on the pictures. I'm planning to put pearls on the net, in blue sections. The first test of getting a pearl over the mesh was successful, but it will still need some rows before I do it for real. I'm really, really excited to find out whether it works like I planned it!

It has the same huge 4 mm mesh size, but is worked with much thinner thread, so it's much closer to historical pieces. The thread might still be thinner, and the mesh could be smaller, but I'll take it slowly for a change. Plus it's not so easy to get superthin yet resilient silk thread.

Here you see the new net after nine hours of work. Cast-on went a lot smoother this time, since I stuck to the tried and tested method described by Therèse de Dillmont. Even though, it felt really fiddly due to the thin, fly-away threads (and since I did this out of doors, there actually was some wind to "help" from time to time). I'd say that netting with the fine thread does take a bit longer than with the thicker thread, even with identical mesh size and numbers, because the thin silk likes to crumple or curl up, and I'm a bit more careful with the fine net than with the sturdier one. Hence a little less work speed.

Cast-on loops are about 2 cm long, and cast-on was on a thick linen ply. A second loop of the linen thread serves as holding loop. I have switched completely to working with my new "Nähstein" now that I have finished making it. In case you didn't ever hear of that before, a Nähstein is a weighted pincushion that serves as the third hand to hold netting work or sewing work - and it's so practical! I'll post a picture of the Nähstein in action as soon as I get somebody to take it.

The new net is worked in YLI Silk 100, with the same netting needle and the same mesh stick that I used for the last one (hence the same mesh size). It is worked in the round, and on this picture you can or cannot see the meshes where transition into the next row takes place. Click on the picture to see it larger. Making one full round with the full number of mesh loops takes me about half an hour - so you can go ahead and try to calculate how long the whole thing would take with straightforward netting all through.

I used the hairnet with the embroidered arms as an inspiration - that is why you see the first rounds of blue netting on the pictures. I'm planning to put pearls on the net, in blue sections. The first test of getting a pearl over the mesh was successful, but it will still need some rows before I do it for real. I'm really, really excited to find out whether it works like I planned it!