Well, the plan for the Madder Baselines is about done - the rest of the planning will have to be done as soon as we know how many samples there will be to handle, and then go for a last check through the long list of steps - before following them through to, hopefully, a nicely colourful end.

Meanwhile I have a second template to turn into a plan and protocol: the template for a mordanting experiment. Common Horsetail is said to contain quite a bit of alum, so it is in theory a replacement for mineral alum which may not have been available everywhere. However, it's not really clear if the horsetail is really suitable for this, mostly because there's no recipe that tells us about amounts necessary, or if there was any other preparation done before using it. Or at least I have not been able to find any...

So the idea was to try out if the plant will work as a mordant, and if yes, how much of it is needed. Because even if it's available, if you need ten times the amount of wool weight to have enough alum, well... that would mean 10 kg of the dried plant for a single kilo of wool, and if you've ever woven fabric, you know that a kilo is a puny amount.

I can think of three different methods of using the plant straight away: as it is (just dried, then soaked, and maybe boiled a bit previously to better get out the contents), fermented, or (which would also reduce the bulk of it) burnt to ashes (which should still contain the metal, though maybe in a different form).

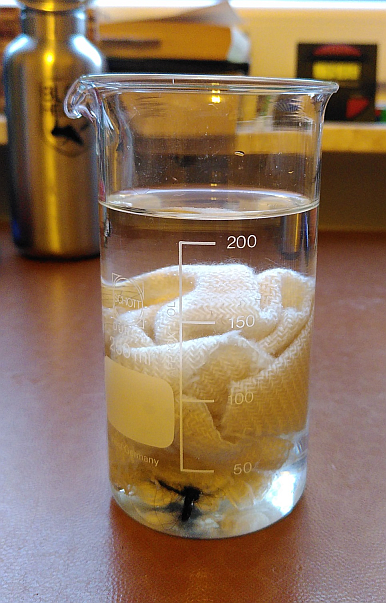

Obviously, the burning and the using as is do not need extra prep time, but the fermenting does. I'm happy to report that the 100 g of plant that I put into 7 litres of rain water are doing what they are supposed to be doing: Making bubbles and working on changing their smell.

It's not an unpleasant smell (at least not yet), but it is definitely much different from the smell it had at the start (like dried horsetail, but thank you, Captain Obvious). I'm very, very curious already to find out how (or if!) all this will work!