Now that I'm slightly over the half-way mark with my "learn how to knit" project, I've already fallen in love with something to make after that.

It is a pair of socks, with free pattern on the Internet. But no ordinary socks - no, they are Alice-in-Wonderland-Illusion-Socks (pattern and pics in pdf). And of course there are questions... like "can I use the wool from my stash* for socks, even if it's a bit thick, if I use really thin knitting needles?" and "how can I eliminate that jog?"

Now I already hate jogging as in "run to get somewhere faster" - my knees and me, we're just not made for that. And jogging in knits? Not so grand as well. So I was looking around a bit the Internet on how to eliminate the jog, and there's a method called "jogless jog" - which helps. Basically, jogless jogging means gently mangling or mushing the stitches around the jog to conceal it. But there's still a jog, and there's still fiddling with the colour change and carrying up of threads. (Nice explanations of jogless jogging can be found at TechKnitter's blog.) And the structure of circular knitting does allow for truly jogless stripes - with only a slight colour-coming-in-jog at the start and the end.

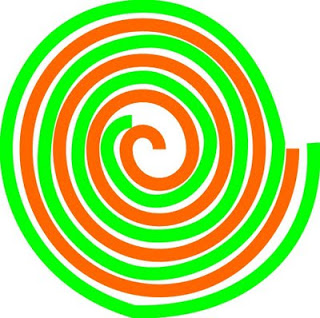

Now, technically, knitting in-the-round is knitting a spiral. For normal colour changes as for stripes, you are breaking the spiral to change from colour A to colour B. Imagine knitting in the round with a lot of increases so your round turns out flat, and it will look like this:

In sock knitting, this would be one round orange, jog, one round green, jog, ... and so on. You are trying to knit rounds of colour in a true spiral, breaking the spiral. Rounds of colour can be done easily, and jog-lessly, on a rounds-based technique like netting, but not on a spirals-based technique like knitting or nalbinding (and not in netting if you mush your meshes at the beginning so you can net spirals).

Breaking the spiral will always result in a jog. For thick, solid stripes, that isn't too bad. But for one-line or two-line stripes, that means the jog is all or half the stripe thickness if it's not eliminated.

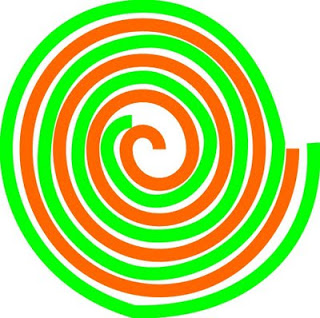

But why break the spiral at all? Why not just insert another spiral? That would look like this:

In sock knitting, this would look like one round orange-one round green-one round orange and so on. No jogs - because you are not breaking the spiral.

In sock knitting, this would look like one round orange-one round green-one round orange and so on. No jogs - because you are not breaking the spiral.

You just add another spiral for each coloured row - so for illusion knitting, that would mean four spirals (two of colour A, two of colour B) each coming from one ball of yarn. Which is more or less the limiting factor of this technique: one ball for each spiral, making it a ballsy technique, so to say.

Of course I had to try it out (and that's why this blog post is so late today):

You can see the very sloppy join of the cast-on (the bump), and you should be able to see where the additional three spirals come in at different places at the bottom of the tiny tube. You cast on, knit to the end of your solid part, and then you just knit in the other colours/spirals.

Let's say you are knitting in the round with five needles (four in the knitting, one working needle) and want to have two-row spirals. This means you stop at where you want the colours to come in, with your current working thread (colour A) at the end of one needle (and the fifth needle free). Now usually, you would turn your work clockwise and continue on the next needle. Instead, turn counter-clockwise and knit in the second thread of colour A, right across the needle, turn clockwise and knit across the next needle. You now have both colour A threads stacked on top of each other. Now turn your work 180° counter-clockwise and knit in the first ball of colour B - across that needle, across the needle where you brought in the second colour A, across the third needle where you already stacked up both colour A threads, making your stack even higher. Now you can turn clockwise again, and on this needle you knit in your second colour B thread. You can knit this all around until you reach the huge stack - and from now on, whenever you find yourself on top of that stack, just take the bottommost working thread and work one round, switch thread, and so on and so on. That's it. The last stitch you are knitting into (on top of that stack) will be quite loose, but the tension adjusts itself when you take up each of the threads to work with them. And the little stack of current spiral ends also makes for a wonderful rounds marker.

To end spiraling, just stop knitting the spirals one by one, preferably at the place where you started it, to make the complete thing approximately the same length all over. Putting in a short-row heel when starting the sock at the toe shouldn't pose too large a problem as well (I'll figure that out after I've found out whether I can use my stash yarn or not). And then - Illusion Socks in Ballsy Spirals method!

* Yes, I already have a significant yarn stash. Yes, that shouldn't happen if you are not a knitter. However, I started buying those wonderful, naturally-dyed yarns ages ago when I would still think of using them for tablet weaving, and I sort of got hooked on the colours and just needed my regular yarn fix afterwards.

It is a pair of socks, with free pattern on the Internet. But no ordinary socks - no, they are Alice-in-Wonderland-Illusion-Socks (pattern and pics in pdf). And of course there are questions... like "can I use the wool from my stash* for socks, even if it's a bit thick, if I use really thin knitting needles?" and "how can I eliminate that jog?"

Now I already hate jogging as in "run to get somewhere faster" - my knees and me, we're just not made for that. And jogging in knits? Not so grand as well. So I was looking around a bit the Internet on how to eliminate the jog, and there's a method called "jogless jog" - which helps. Basically, jogless jogging means gently mangling or mushing the stitches around the jog to conceal it. But there's still a jog, and there's still fiddling with the colour change and carrying up of threads. (Nice explanations of jogless jogging can be found at TechKnitter's blog.) And the structure of circular knitting does allow for truly jogless stripes - with only a slight colour-coming-in-jog at the start and the end.

Now, technically, knitting in-the-round is knitting a spiral. For normal colour changes as for stripes, you are breaking the spiral to change from colour A to colour B. Imagine knitting in the round with a lot of increases so your round turns out flat, and it will look like this:

In sock knitting, this would be one round orange, jog, one round green, jog, ... and so on. You are trying to knit rounds of colour in a true spiral, breaking the spiral. Rounds of colour can be done easily, and jog-lessly, on a rounds-based technique like netting, but not on a spirals-based technique like knitting or nalbinding (and not in netting if you mush your meshes at the beginning so you can net spirals).

Breaking the spiral will always result in a jog. For thick, solid stripes, that isn't too bad. But for one-line or two-line stripes, that means the jog is all or half the stripe thickness if it's not eliminated.

But why break the spiral at all? Why not just insert another spiral? That would look like this:

In sock knitting, this would look like one round orange-one round green-one round orange and so on. No jogs - because you are not breaking the spiral.

In sock knitting, this would look like one round orange-one round green-one round orange and so on. No jogs - because you are not breaking the spiral.You just add another spiral for each coloured row - so for illusion knitting, that would mean four spirals (two of colour A, two of colour B) each coming from one ball of yarn. Which is more or less the limiting factor of this technique: one ball for each spiral, making it a ballsy technique, so to say.

Of course I had to try it out (and that's why this blog post is so late today):

You can see the very sloppy join of the cast-on (the bump), and you should be able to see where the additional three spirals come in at different places at the bottom of the tiny tube. You cast on, knit to the end of your solid part, and then you just knit in the other colours/spirals.

Let's say you are knitting in the round with five needles (four in the knitting, one working needle) and want to have two-row spirals. This means you stop at where you want the colours to come in, with your current working thread (colour A) at the end of one needle (and the fifth needle free). Now usually, you would turn your work clockwise and continue on the next needle. Instead, turn counter-clockwise and knit in the second thread of colour A, right across the needle, turn clockwise and knit across the next needle. You now have both colour A threads stacked on top of each other. Now turn your work 180° counter-clockwise and knit in the first ball of colour B - across that needle, across the needle where you brought in the second colour A, across the third needle where you already stacked up both colour A threads, making your stack even higher. Now you can turn clockwise again, and on this needle you knit in your second colour B thread. You can knit this all around until you reach the huge stack - and from now on, whenever you find yourself on top of that stack, just take the bottommost working thread and work one round, switch thread, and so on and so on. That's it. The last stitch you are knitting into (on top of that stack) will be quite loose, but the tension adjusts itself when you take up each of the threads to work with them. And the little stack of current spiral ends also makes for a wonderful rounds marker.

To end spiraling, just stop knitting the spirals one by one, preferably at the place where you started it, to make the complete thing approximately the same length all over. Putting in a short-row heel when starting the sock at the toe shouldn't pose too large a problem as well (I'll figure that out after I've found out whether I can use my stash yarn or not). And then - Illusion Socks in Ballsy Spirals method!

* Yes, I already have a significant yarn stash. Yes, that shouldn't happen if you are not a knitter. However, I started buying those wonderful, naturally-dyed yarns ages ago when I would still think of using them for tablet weaving, and I sort of got hooked on the colours and just needed my regular yarn fix afterwards.