When I learned tablet-weaving, I used either beer mats or butchered playing cards. For my small hands, beer mats are definitely too large, so I went over to playing cards cut up and punched with holes for good. They are slim, lightweight, quite sturdy and cheap - the only problem is that you have to cut them to squares and punch holes. And as I'm a bit demanding about my hole placement, wanting them all in the same place, this did always take some time; time spent to prepare weaving equipment that was obviously so not historical. So I've been looking for alternatives for a long time now.

I tried to weave with small (really small) bone tablets one time - they are nice, smooth and good-looking, but they are also tiny with their side length of 2,4 cm, and I did not manage to get a smooth weaving sequence with the tiny things in a band with more than just 5 or so tablets. I also got wooden tablets made as a present once - again, carefully cut, bored and sanded for smoothness, and just the right size to weave. However, wooden tablets add a huge amount of bulk to the tablet-stack and are quite heavy.

So despite all these tries to use more medieval materials for the tablets, I always returned to my trusty playing-cards for weaving work. Since I don't weave for show on medieval events, it was never a problem. But there's a difference between not needing and not wanting... and I wanted.

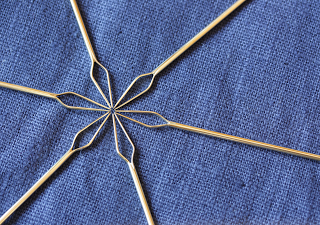

And now I have - and I have to spare, so they are on offer at the market stall. I present to you the museum-compatible, slim alternative to cardboard and playing-card tablets: Weaving tablets made of parchment.

These tablets measure 6 x 6 cm, a convenient size when weaving and large enough that you can handle them well and even weave with the tablets standing on the corners, for tubular or other special weaving actions. The parchment is prepared by hand, in one of the last traditional parchment manufactury. In this case, it is calf parchment. Rounded corners for smooth turning, large holes for ease of setting up the warp.

The tablets, being parchment, can be marked, coloured, scribbled on - whatever you desire. With a thickness of about 0,6 mm for most of them, they are slim enough so that handling a larger stack is easily possible - but stiff and wide enough to grasp them easily. So... no more excuses about not having acceptable weaving tablets to work with!

I tried to weave with small (really small) bone tablets one time - they are nice, smooth and good-looking, but they are also tiny with their side length of 2,4 cm, and I did not manage to get a smooth weaving sequence with the tiny things in a band with more than just 5 or so tablets. I also got wooden tablets made as a present once - again, carefully cut, bored and sanded for smoothness, and just the right size to weave. However, wooden tablets add a huge amount of bulk to the tablet-stack and are quite heavy.

So despite all these tries to use more medieval materials for the tablets, I always returned to my trusty playing-cards for weaving work. Since I don't weave for show on medieval events, it was never a problem. But there's a difference between not needing and not wanting... and I wanted.

And now I have - and I have to spare, so they are on offer at the market stall. I present to you the museum-compatible, slim alternative to cardboard and playing-card tablets: Weaving tablets made of parchment.

These tablets measure 6 x 6 cm, a convenient size when weaving and large enough that you can handle them well and even weave with the tablets standing on the corners, for tubular or other special weaving actions. The parchment is prepared by hand, in one of the last traditional parchment manufactury. In this case, it is calf parchment. Rounded corners for smooth turning, large holes for ease of setting up the warp.

The tablets, being parchment, can be marked, coloured, scribbled on - whatever you desire. With a thickness of about 0,6 mm for most of them, they are slim enough so that handling a larger stack is easily possible - but stiff and wide enough to grasp them easily. So... no more excuses about not having acceptable weaving tablets to work with!