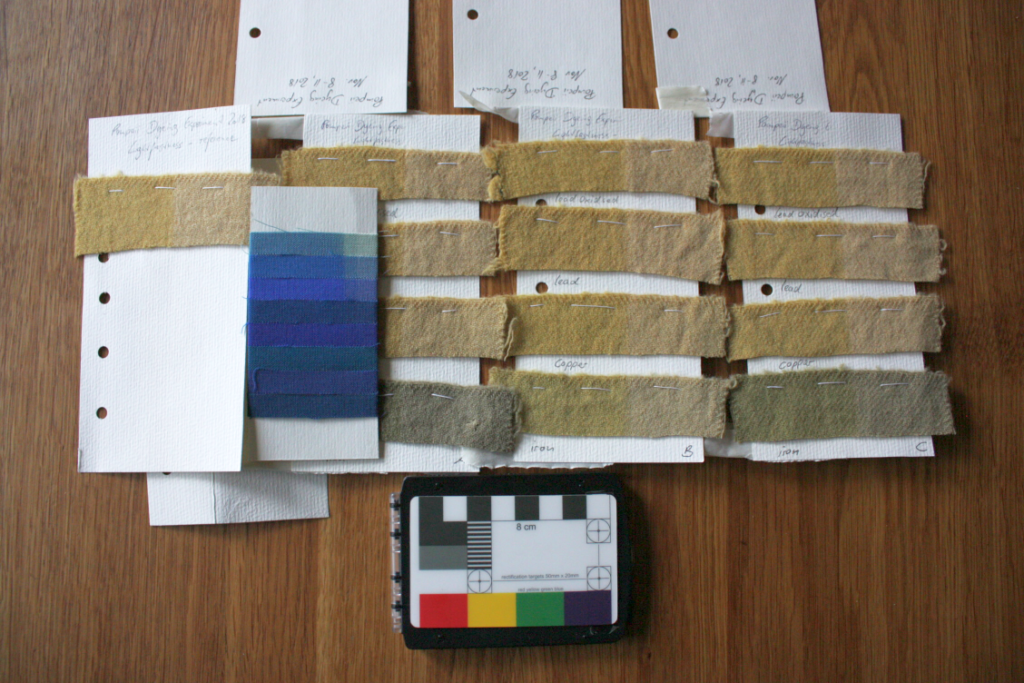

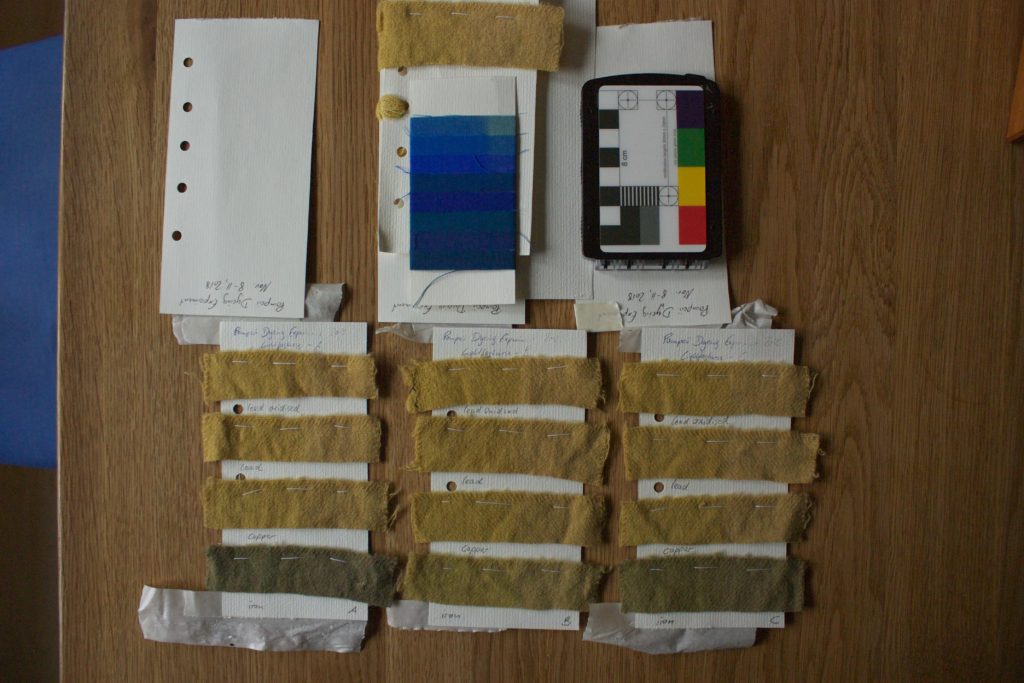

So I've been busy doing video stuff, including the cutting and editing, and doing all the other bits and things necessary to prepare. What ate a lot of time - much more than I had expected - was making a colour sample card as the object to go in there to represent the Pompeii Dyeing Experiment. This started in 2012 with a first run, and there was an add-on made in 2013, followed by two more runs of the experiment in 2016 and 2018. The aim was to find out how a metal kettle would influence the results of the dyeing process, both due to the presence of metal in the mordanting bath, in the dyeing bath, and in both.

For the exhibition, I wound the samples onto strips of cardboard, grouped by kind (mordant, dye, both) and by metal. Nine turns of the thinner wool, used in 12/13 and 2018, and six turns of the thicker wool used in 2016. All neatly in the same position on each strip...

...and it's amazing how much of brain such a simple task can eat.

My personal main takeaway from this experiment, by the way, is the importance of repetition - plus a much higher appreciation of just how much variation natural materials can introduce, and how much of a role sheer luck plays in even the best controlled experiment.

In the 2012 run, we ended up with a reddish colour on the yarn dyed in the copper and the clean lead kettle - which made a kettle made from lead with an oxide layer on the surface the neutral kettle, very close to the actual control dyed in a glass jar with no metal plate added at all. In the following runs, we were never able to reproduce that reddish colour - apart from the iron, our samples all turned out pretty yellow, and much the same across all kettles. If not for that chance aberration in the first run, we would have thought that there is no real difference between the kettle materials, at least not when using madder or birch leaf as a dye.

I'm actually tempted to run the experiment again next time that the Forum will happen (2021, I'm looking at your autumn with a critical eye!), with weld as a dyestuff instead of birch leaf, and see if results are giving us a clear difference there.

Anyway - the card has been finished, which involved lots of glueing, and the use of some of my bookbinding equipment, and now it will go on its way to Asparn!

[caption id="attachment_5775" align="alignnone" width="169"]

Pressing with weights until the glue has set...

Pressing with weights until the glue has set...

Some of the silks dyed for the project, still in skeins.

Some of the silks dyed for the project, still in skeins.